Calling yourself ‘Hammer Films’ can work for you and it can work against you.

On the one hand it gets you and your films more attention from the first than any other fledgling independent film company could dream of – would you have even heard of Beyond The Rave otherwise? – while on the other it automatically creates a weight of expectation that is almost impossible to honour.

Some will want you to succeed whatever, just because of the name. Others, probably more, will want you to fail whatever, for the same reason.

Then there are those who’ll say, simply, what’s the point?

You can call yourself what you like, but it won’t result in any kind of instant metamorphosis. It’s interesting that there is an Ealing Films currently trading too, but oddly subjected to neither the same scrutiny nor the same challenging response to its product. There is a protective passion for Hammer out there that is almost impossible to please. Stray too far from the classic template and they’ll call you senselessly revisionist, pastiche it too accurately and they’ll call you hopelessly dated.

I suppose if I belonged in any of the categories above it was the ‘what’s the point?’ one, though as a certain devotee of Hammer House of Horror I had no inflexible objection to the name’s revival, and on the whole I liked the idea. But I wasn’t all that excited about the films themselves. I managed about two minutes of Beyond the Rave (I gather that’s a world record) and a heroic fifteen or so of Wake Wood (which it turns out isn’t really a Hammer film at all).

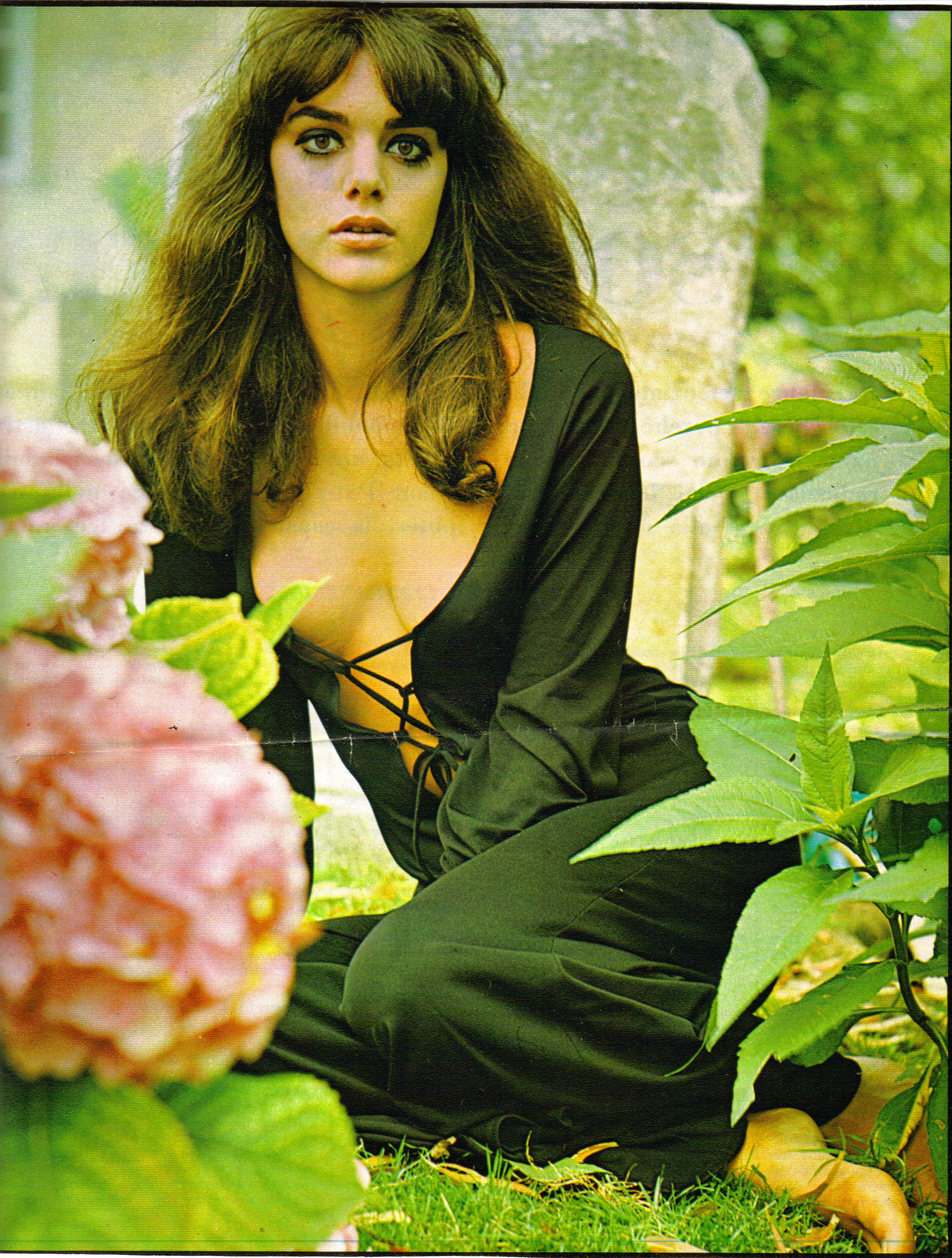

But The Resident I enjoyed, because it worked efficiently within its remit, and obviously because it brought Christopher Lee back. The New York setting was a touch provocative (though it shouldn’t be forgotten that the original Hammer psycho-thrillers it referenced were by no means predominantly English-set), and however much a casting coup Hilary Swank may have been, they should have known that you really need a dolly bird for woman-in-jeopardy roles.

Still, I liked it overall, but much more importantly, I found when that red Hammer logo flashed across the screen that I did care after all, and I do like seeing the name up there again.

Still, I liked it overall, but much more importantly, I found when that red Hammer logo flashed across the screen that I did care after all, and I do like seeing the name up there again.So that’s why I went to see The Woman In Black last night in a well- rather than ill-disposed mood.

Better yet, I came out the same way.

It’s a film that has done the seemingly impossible: justified the use of the Hammer name, honoured the traditions of the studio’s past, evoked much of its style, and at the same time managed to appeal to a broad, modern audience that have no interest in, or perhaps even awareness of, the original films. As a film it’s good, as a juggling act it’s amazing.

There have been some tellingly dogmatic objections, of the sort to which even as hopelessly romantic a reactionary as I can raise only a weary ‘so what?’ in response: the original Hammer never made a supernatural ghost story; they cut the film to get a 12 certificate; Daniel Radcliffe is too young; George Woodbridge isn’t in it. (Okay, I made the last one up, but you get the idea.)

These are a priori obstacles, the kind of thing no amount of competence in the actual product can circumnavigate.

I can’t think of any defining reason why they wouldn’t have made a ghost story back at Bray; and they certainly had a long and fascinating history of cutting their films to match a certificate (including an A certificate once in a while). Curse of Frankenstein is a 12 these days too, and all I can say is that if I had seen Woman in Black at twelve years of age I’d still be talking about its seminal influence on me now (the way I do about The Ghoul). You won’t go short on scares, believe me. You will go short on people being lashed to chairs in basements and tortured with garden tools, but then that’s not what you came for, is it?

There are the expected anachronisms of course, of the sort which no modern film set in the past could now be expected to avoid, annoying though they are all the same: designer stubble, men walking about in the rain without hats, characters suggesting they “get the hell out” of places, and ugly modern metaphor-speak (Radcliffe’s boss urges greater commitment from his employee on the grounds that they “don’t carry passengers”).

And Wizard Boy is too young; there’s no point pretending he isn’t. But neither would it be right not to add that, given that initial handicap, he delivers a truly excellent performance that does everything possible to make you forget, or at least excuse, his fundamental unsuitability for the role. His commitment and intensity cannot be faulted – his facial acting alone has to carry a good fifty percent of the film – and if he never quite convinces us he’s a widowed lawyer with a four year old son, well… Julie Ege wasn’t my mind’s idea of an Edwardian feminist adventuress. Can’t say that worried me unduly either.

And Wizard Boy is too young; there’s no point pretending he isn’t. But neither would it be right not to add that, given that initial handicap, he delivers a truly excellent performance that does everything possible to make you forget, or at least excuse, his fundamental unsuitability for the role. His commitment and intensity cannot be faulted – his facial acting alone has to carry a good fifty percent of the film – and if he never quite convinces us he’s a widowed lawyer with a four year old son, well… Julie Ege wasn’t my mind’s idea of an Edwardian feminist adventuress. Can’t say that worried me unduly either.These are precisely the kind of eccentricities that Hammer must be allowed.

The rest of the film? Well, it’s not especially original and it’s not especially ambitious, so hyperbole would sit ill on its frail shoulders. But in terms of the limits it sets for itself, it’s really hard to find anything wrong with it at all. Almost everything works a treat.

Even rendered in tacky digital format, the art direction is astounding, the photography is rich, the locations are beautifully atmospheric. Did you not dream of seeing a Hammer character making his way up and down a baroque staircase left of frame again? Dream no more!

Even rendered in tacky digital format, the art direction is astounding, the photography is rich, the locations are beautifully atmospheric. Did you not dream of seeing a Hammer character making his way up and down a baroque staircase left of frame again? Dream no more!At least two of the big scare moments work better than anything comparable in any of the similar films to which this has been compared, and the lingering sense of dread that strings them together is better yet. There’s even a slightly sappy ending that, a meaningless close on the Woman in Black’s face notwithstanding, honours the original Hammer’s commitment to ultimately restored order, even to restored order within a framework of Christian dogmatics.

I liked the casting, too, which seemed to me chosen by the classic Hammer method: an attention-catcher in front, sturdy support from traditional talent (Ciaran Hinds is splendid) and a fine third-row of well-chosen rhubarbers (David Burke, probably tv’s best ever Dr Watson, gets a line or two as the village bobby; Victor McGuire gets one as an anguished father).

I liked the casting, too, which seemed to me chosen by the classic Hammer method: an attention-catcher in front, sturdy support from traditional talent (Ciaran Hinds is splendid) and a fine third-row of well-chosen rhubarbers (David Burke, probably tv’s best ever Dr Watson, gets a line or two as the village bobby; Victor McGuire gets one as an anguished father).It’s good to see them, and they have the feel of a new Hammer repertory. If any of them showed up again in the next one it would be wonderful. (As my compadre Mark notes in his review of the film here, it would be good if they used Radcliffe again too, perhaps in a more villainous capacity, playing his easy good looks against expectation in the Shane Briant manner.)

It is in such matters as these that the true Hammer flavour can most usefully be recalled. What the studio really needs is an overarching identity that links its new films to each other, rather than something that links any of them to the past.